Every year, 20 million tonnes of fish caught in nets are either thrown back into the sea, often dead, or brought back to the quayside but not marketed. This is a significant waste and above all a serious problem for the environment and wildlife. This is what motivated the GAME OF TRAWLS project (Giving Artificial Monitoring intElligence tO Fishing TRAWLS) which will allow the sorting of fish in the net still in the water. The Ifremer institute of Lorient in partnership with the company Marport and the Departmental Committee of maritime fisheries and marine breeding of Morbihan, called upon the specialists in detection and neural networks of the University of Southern Brittany.

Trawling has a bad image: it is criticized for its highly invasive practices on ecosystems and the number of involuntary catches. Solutions are proposed to reconcile economic interests and environmental protection. Julien Simon, from Ifremer’s Fisheries Technology and Biology Laboratory, explains:

“A trawl net is like a large landing net, it is towed behind the vessel for several hours without having any knowledge of what goes into it in real time, i.e. are they species that are targeted by the fisherman or not.”

In order to help fishermen reduce their impact, Ifremer called on experts in detection and neural networks from the University of Southern Brittany and more specifically on the Obelix team from IRISA (Institut de Recherche en Informatique et Systèmes Aléatoires), whose objective is the processing of complex images for environmental purposes.

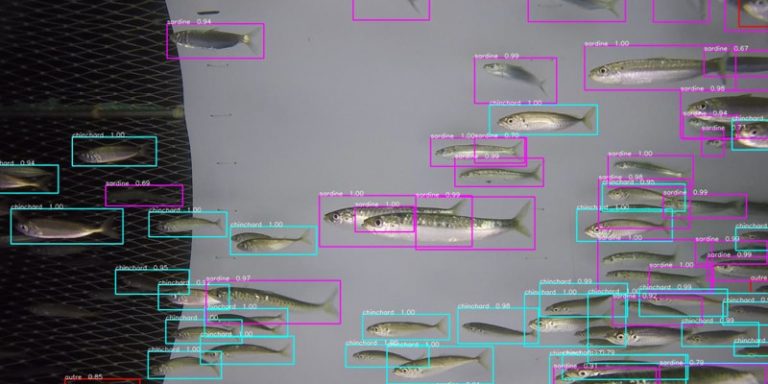

The recognition of living organisms in real time and, what’s more, in motion in a poorly lit environment is complicated. To do this, computer scientists assemble neural networks by incrementing a large amount of data.

Luc Courtrai, senior lecturer in computer science, specialist in remote sensing and neural networks, and member of IRISA explains:

“Existing neural networks are trained on this domain, but to classify a species, the image is no longer enough. We need different modes of input: water temperature, video, acoustic, geographical data, water PH, etc.”

Jean-Christophe Burnel, study engineer at IRISA, adds:

“3D cameras are being developed by the company MARPORT. Using acoustics, they can recreate the shape of the fish, the shoal, and thus deduce the species.

25 species are currently integrated

Since February 2019, Irisa and Ifremer have been collaborating on this project, whose test phases and end date are set for December 2021. The team started by integrating four pelagic species living between the surface and the seabed (sardines, anchovies, horse mackerel, mackerel) and about twenty bottom species (shrimps, langoustines, galatheas, sea anemones…). Luc Courtrai explains:

“The interest for fishermen is, for example, to distinguish langoustines from galatheas that are not marketed.”

Sensors and cameras installed at the entrance of the trawl net will allow the counting and measurement of catches, and thus decide to keep the catch or to activate the opening of a trap using the software. Éric Guygniec, head of the Breton shipping company Apak and partner in the project, points out:

“I’m not interested in having the fish on the deck and sorting it once it’s dead, I prefer to sort it on the bottom. With such a device, we know at all times what goes into the net, the size of the fish and the species, and if the species is not of interest to us, we can open a trap door.

The smart net is expected to be on the market in 2025, but fishermen and trawler companies point to the high costs of this system.

Ifremer is also testing a pelagic net, which moves between the surface and the bottom without coming into contact with the latter in order to preserve the ecosystem, also equipped with cameras and sensors. Julien Simon explains:

“Depending on the presence of targeted or non-targeted species, the trawl net will switch to fishing mode or flight mode to avoid impacting the seabed.”

Translated from Le deep learning pour développer des filets intelligents de chalutiers au coeur du projet Game of Trawls